Beats, Beats, and Beats

If there’s one thing we can all agree on, it’s that you can’t beat a piece that has a good beat. The problem is, we can mean a handful of different things when we say the word “beat.” Over the next few Music Alive! emails, we’ll explore a few of the things we can mean when talking about beats. Today’s email will focus on Pulse.

When we think of “the beat of the music,” we’re often referring to its pulse. As the cognitive psychologist Stephen Handel notes, “Pulse is typically what listeners entrain to as they tap their foot or dance along with a piece of music.” Anytime you find yourself tapping your foot, bobbing your head, or even lightly conducting along to the beat, you’re noting and riding along with the pulse of a piece.

Pulse

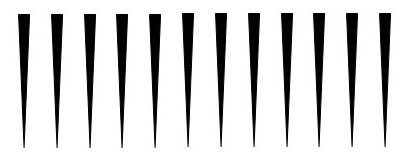

We’re going to use a couple of diagrams in this exploration, and the core of the diagrams will be a symbol that indicates any rhythmic event. Think of the below symbol as any rhythmic sound you can imagine (ie. a drum hit, cymbal crash, or tap on a desk):

In order to create the beginning of a pulse, we’ll need a second rhythmic event after the first. When that second event occurs determines the speed of our pulse:

Now that we’ve got two rhythmic events in a row, we can continue with other rhythmic events ad nauseam, with each rhythmic event spaced the same distance apart. This is where we get the beat, the pulse of the music. Every piece of music, like every person, has a pulse. Count the twelve symbols below at regular intervals from each other, tapping your finger as you count:

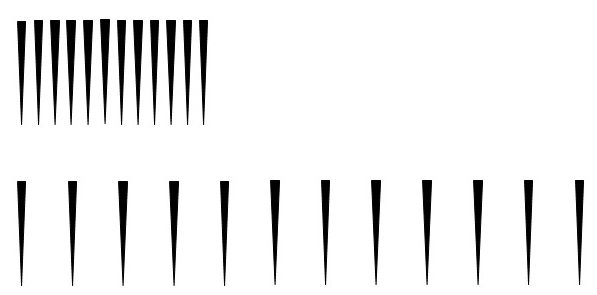

Once we’ve established that regular pulse, we can do lots of things with our rhythmic events. For example, we can space the rhythmic events closer together or farther apart, as diagramed below. Changing the distance between the rhythmic events increases or decreases the tempo of the music (Italian for “time”), which is the musical term for the speed of the music. As you count the two examples below, tap your finger faster for the symbols spaced closer together and slower for the symbols that are farther apart:

Musicians describe the tempo of a piece of music by indicating the beats per minute, or BPM. This is a specific equation of the number of rhythmic events that happen over the course of 60 seconds. For example, if a piece of music has one rhythmic event every second, it has a tempo of 60 BPM. A piece with two rhythmic events per second has a tempo of 120 BPM, one and a half rhythmic events per second is 90 BPM, and three is 180 BPM.

On December 5, 1815 German inventor Johann Maelzel patented his “Instrument(s) or Machine(s) for the improvement of all musical performance, called the metronome.” It was this invention that enabled many musicians the ability to truly dial in the tempos at which their music should be performed. Today, you can access a metronome as easily as typing “metronome” into Google!

While all of this describes the speed pulse of a piece, the true beauty of thinking about that speed is when we apply it to the music we already know and love. Below are a handful of pieces that have specific tempos. Listen to each and then consider: What are the tempos of some of your favorite pieces? Are they similar?

~60 BPM – Bach: “Air on the G String”

~90 BPM – Carl Perkins: “Blue Suede Shoes”

~120 BPM – Journey: “Don’t Stop Believin'”

~160-180 BPM – Chuck Berry: “Johnny B. Goode”

~240 BPM(!) – Benny Goodman: “Sing, Sing, Sing”

Bonus Listening!

Even COVID-19 can’t stop the beat! Watch the video below as “The Actors Fund Isolation Players” perform the rousing finale from the musical Hairspray, “You Can’t Stop the Beat” (~170 BPM). This energetic rendition has brought smiles to the faces of more than 600,000 people; we hope it brightens your day too!